Continuing and ending my mini-series on how to land, this article focuses on flying a good traffic pattern: the military Overhead.

The Overhead Pattern is better than a civilian box pattern for a multitude of reasons, the most important reason directly applies to RC flying: all pattern references are based directly off of the runway.

In a civil box pattern, references are derived from the particular geography surrounding the field. A house with a red roof might define the downwind ground track, then turn at the water tower, follow the river jog, etc. That is because civilians can become intimately familiar with their home drome, but military pilots must be able to land consistently on any runway the world has to offer on the first attempt.

Another reason the civil box is different is the possibility of positive control versus the certainty of passive control. Positive control means some entity other than the aircraft may determine pattern priorities. Passive control means aircraft resolve their own conflicts without any the need for audio communication, only visual comm is required to sequence the pattern safely.

RC flying only allows the pilot a runway-based perspective, so the military Overhead is the perfect pattern to fly.

The second reason the military overhead could also apply to RC, depending on one’s circumstances: it is tight. The reason the pattern needs to be tight is forward operating base airfield defense.

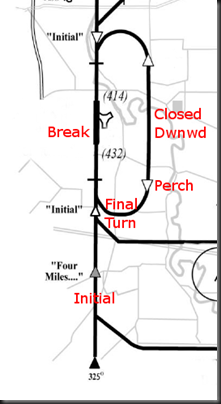

Military airfields are primary targets, and defending a lot of ground is difficult. The tighter the pattern is to the landing strip, the less area there is to defend. Aircraft make their Initial approach the field at the speed of heat to make potshots difficult, then enter a 180 degree break turn, called the “Break” for short, then fly a tight downwind leg called “Inside (or Closed) Downwind” past a Perch point and into a Final Turn onto Final to land.

Taking the (underlined) pattern legs one at a time and in order:

Initial – An “initial” approach to the field that is aligned with the landing runway and landing direction (usually up wind). Initial is anywhere from 2 to 20+ miles long and from 1000’ AGL to several thousand feet in the air. In combat, it isn’t unusual to approach the field between 500-600 knots.

The Break Point – As you approach the airfield on Initial, the Break point is the point above your intended touchdown point directly above the runway. In air-to-air lingo, a “break turn” is defined as your quickest tightest turn usually performed in idle while dispensing chaff and flares. Idle power let’s you cash in airspeed chips for min radius, assuming you start above your airplane’s corner velocity. Idle power also cools the plane to minimize any IR signature you might present to heat seekers. The same consideration applies to the pattern break point; manpads are everywhere.

If you are going to be too close to another aircraft on Inside or Closed Downwind, do not Break. Carry straight through the Break Point then resume VFR navigation to re-establish yourself on Initial. Rinse and repeat until you have a safe opportunity to Break.

The declining turn radius of your fast airspeed from Initial to a slower airspeed rolling out on Inside or Closed Downwind defines your lateral displacement from the runway. Your faster, larger radius Break Turn provides the right lateral displacement from the runway for a slower Final Turn, along with some margin for error.

Inside or Closed Downwind – Typically displaced less than a mile from the runway. Landing gear must come down before the Perch Point, with flaps generally tracking to an intermediate position. Closed Downwind is the ideal time to trim the airplane up for a slower airspeed, assess the winds and apply crab to maintain ground track.

This pattern leg is called “Closed Downwind” when you arrive from the “Closed Pull-Up” following a touch and go, while it is called “Inside Downwind” when arriving from Initial via a Break.

The Perch Point – A point that defines the end of Closed Downwind and the beginning of the Final Turn. On a no-wind day, the Perch Point is exactly even with your intended roll-out point on Final, that is, the point that ends your Final Turn and starts Final. The Perch is the last point flown at pattern altitude; it is all down hill from there.

Final Turn – A 180 degree descending turn to Final. The Final Turn is the first time to start considering your runway aimpoint. Although your flight path is not pointed directly at your Aimpoint until completion of the Final Turn, your altitude trend generally points at your Aimpoint from the Perch Point downward.

Fly an airspeed that is fast enough to turn while configured for landing. If you feel a stall developing, roll out to wings level, apply full power and climb straight ahead disregarding any pattern ground track.

Final – A short approach to land. Approaching wings level, slow down immediately to establish your final approach speed. Set the throttle and trim the plane up so it flies toward Aimpoint 1, hands-off.

Note that landing is generally assured once the airplane is established on Initial, even if you lose the engine(s). On long initial, engine-out, consider a straight-in.